Media Platform &

Creative Studio

Magazine - Features

In conversation: Dot Young

Joana Alarcão

In this interview, Dot Young discusses their sculptural practice, which explores our relationship with the environment. From reflecting on humanity's impact to advocating for environmentally sympathetic materials like Heritage Japanese papers, Dot's work embodies a commitment to sustainability. Currently on sabbatical from the University of London and serving as a lecturer at the Royal Central School of Speech and Drama in London, Dot shares their journey towards minimizing the environmental footprint of artistic endeavors.

25 March 2024

My sculptural practice explores our relationship with the environment in a variety of ways. Through a series of projects my work has previously reflected on the impact humanity has had on our planet, asked where and with whom the responsibility may sit, looked to individuals who work to protect it and celebrated its complexity and beauty.

Currently, my work explores the benefits of the adoption of environmentally sympathetic materials in one's work and reflects on what we as artists can do to minimise the negative impact our work may have on our environment. Currently looking to Heritage Japanese papers as an environmentally sympathetic material, rooted in a relationship with nature, rather than an exploitation of it, I have transitioned my own work from less sustainable practices to a commitment to more environmentally feasible practices.

I am on sabbatical currently from the University of London, where I am a lecturer at Royal Central School of Speech and Drama, and plan to visit Japan later in the year, to further understand the origins of heritage paper production practices in terms of the Shinto religion animism and protection of traditional crafts.

Your sculptural practice delves into our relationship with the environment, exploring themes of impact, responsibility, and beauty. Could you share more about the journey that led you to focus on these themes, and how they manifest in your artistic work?

Becoming a sculptor was influenced by growing up in an engineering household, surrounded by discussions regarding the physical and functional complexities of machinery and the architecture of objects, along with the absorption of an ever-evolving and expanding galaxy of industrial materials and techniques that promised an infinite range of production possibilities.

In many ways incubated and fuelled by the legacy of the Industrial Revolution and unconsciously part of the mid-century surge in human activity, now referred to as the Great Acceleration, I became adept at a multitude of sculptural practices, navigating complex mechanical and chemical procedures, and embracing the contemporary alchemy of modern fabrication techniques.

My enlightenment and commitment to recalibrating my relationship with the environment started when I began tracking the history of manufactured objects, through both their fabrication processes and the sonic fallout expended in their production. The research project, entitled ‘Aurality of Objects’, considered what our relationship might be with objects if we were able to both hear and see the journey of their creation, as featured in the cross-disciplinary writings of the exhibition ‘The Sensorial Object’, Cardiff, Wales.

The first manifestation of this research was ‘Chair - A Life Backwards’ (2013), an art installation, exhibition and sound walk, produced in collaboration with American composer Gregg Fisher, Russian photographer Pavel Legankov, and Sound designer Donato Wharton. This project visually and sonically tracked a British-made oak chair back to the forest where the tree had grown, and explored the complex political and environmental aspects of its production, and the associated implications of globalisation.

This project was followed by ‘Extension’ (2015), produced in collaboration with East German sound artist Lex Kosanke, which tracked the journey of a single human hair, from the Tirupati Hindu Temple in Chennai, Southern India, where it had been offered in an act of tonsure, to its final destination as a hair extension in a beauty salon in south east London. It considered the physical materiality of the hair and the shift in its value as it travelled from a religious context to one involving capitalism.

The projects inspired me to think in a more circular manner about the materials and fabrication processes I use, to develop a more symbiotic relationship with nature, and to re-orientate my practice to emphasise and communicate the importance of sustainability.

Aesthetically, it is important to me that the work I create celebrates the profound beauty of nature, offering the audience a moment to reflect on both the complexities and the minimalistic simplicity occurring in nature and natural forms. The work can be perceived as primarily aesthetic, drawing on traditional sculptural tropes, but it is encoded with environmental messaging. Conceptually, the intention is to offer an awareness of what is under threat, and for the work to act as a conduit to communicate environmental concerns, and as a catalyst for discussion that will hopefully lead to change.

One of the materials you are currently exploring is heritage Japanese papers. What drew you to these materials, and how do they inform the conceptual and aesthetic aspects of your sculptures?

Since the mid-twentieth century, sculptural practices in both fine and applied arts have drawn on the production and application of agile chemicalised and non-biodegradable materials such as polycarbonates, polyurethane, polyester and epoxy resins. These commonly used synthetic resins are extremely flexible and inexpensive, but are also produced using fossil fuels. They are highly flammable, can cause eye, skin and respiratory irritation and, when leaked into the environment, cause damage to soil, rivers, and other water sources. In addition, with their use of styrene, they are carcinogenic.

In seeking materials, that are more environmentally acceptable for my sculptural practice, I looked to those in use before the impact of the Industrial Revolution, before the development of industrialised plastics and the mass production of oil-based products.

During this period, a colleague from Kyoto introduced me to Japanese Heritage Washi papers, most commonly associated with fine art printmaking. In researching the paper’s socio-political history, its inherent qualities and traditional production methods, it became clear to me that, as a material, it addressed the philosophical, conceptual and practical requirements to develop my creative practice.

The environmental lure of Heritage Washi paper is as a renewable resource, with no industrial processes involved in its production. Made from the inner bark of quickly grown and locally cultivated plants, the branches are coppiced annually, meaning that there is no deforestation associated with its harvest. The paper is naturally bleached, and there are no strengthening compounds added as one would find in wood-pulped papers. The traditional production processes have been handed down generationally through families in key Washi producing areas and are considered a symbol of cultural identity.

Conceptually, working with Heritage Washi papers engaged my awareness and understanding of the challenges posed by the Anthropocene, and has caused me to pause and reflect on our eco-system and to consider what we have inherited, what has been lost, and what we can do to ensure environmental protection for the future.

Aesthetically, the Washi paper artwork is informed by the physicality of the material, responding to its flexibility, translucency, fragility and strength. Its transient qualities as a raw material can be interpreted as a metaphor for the fragility of our threatened eco-system. I find the inherent delicacy and structure of the material lends itself to the representation of and the beauty of natural forms, and feel that working with it manually connects me to the artisans who first manufactured it. In working with Washi papers, I aim to invite audiences to reflect on the current environmental challenges we face and what their role may be in them. The initial Washi samples and artworks became the focus of my 2023 exhibition ‘Ephemeral’ at the White Box Gallery in London.

You mentioned plans to visit Japan to understand further the origins of heritage paper production practices, particularly in relation to the Shinto religion, animism, and traditional crafts. What insights do you hope to gain from this experience, and how do you anticipate it shaping your future artistic endeavors?

Visiting Japan will enable further understanding of the cultural heritage of Japanese Washi paper, the artisanal skill involved in its manufacture, and its environmental sustainability.

In working alongside Washi paper makers, experiencing their engagement with a cultural practice that is rooted in their personal and family histories, and in Japan’s national history, I hope to develop a fuller and more nuanced relationship with the material. In understanding the landscape and circularity of the production processes, I hope to develop sculptural responses that can reflect the respect for and relationship with the material that the artisans have, and to develop methodologies for a contemporary and sustainable sculptural practice with which to return to the UK.

Travelling within Japan, visiting key Washi-producing areas, recording the landscape, meeting communities, tracing map routes and undertaking interviews with Washi experts and artists will enable the creation of a photographic and film archive as a resource for future projects.

I also hope to further understand the animistic approaches to landscape that the Shinto belief offers - that being the attribution of conscious life to nature and natural objects, and a belief in spirits that inhabit sacred sites - as I think this will further inform my work.

In going to Japan, I hope to develop future creative UK/Japan collaborations, cultural exchanges, and artistic relationships with Japanese practitioners.

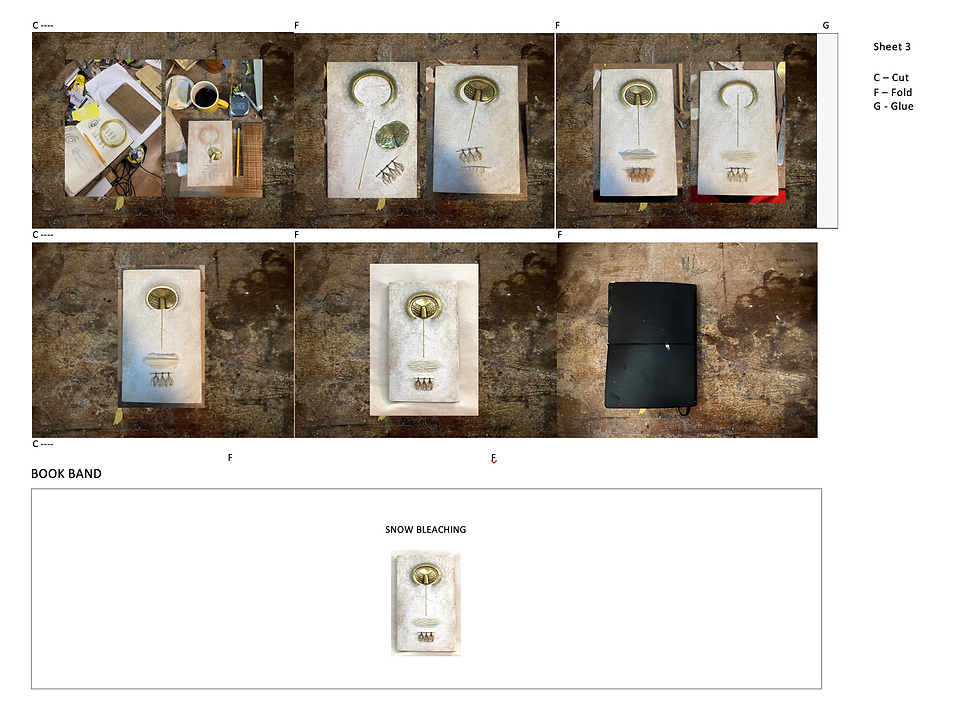

What can you tell us about the submitted project 'The Artists Self-Print Book - ’Snow Bleaching', Washi paper?

My practice has previously leaned towards the ‘artist’s self-print book’ as an adaptable vehicle for storytelling through visual narratives, and as a creative way of sharing the artistic journey of a project. As projects develop, so too do my sketchbooks, accumulating step-by-step photographic records of samples and tests, notes, thoughts, experiments and the development of sculptural forms.

There is a freedom to creating an artist’s book that allows complete ownership of expression with few establishment rules. One could term the genre ‘outsider printing’, which is currently thriving in the form of artists’ ‘zines’.

Key early influences for me were William Blake, the British painter, poet and printmaker, and pioneer of artist-led publishing. He devised his own printing process whereby he could side-step the constraints and traditions of the official printing processes at the time to prioritise his own creative vision. Another is Edward Ruscha, who in 1963 famously side-stepped the high-end art publication market by self-publishing 500 copies of his artist’s book ‘Twenty Six Gasoline Stations’. In an egalitarian fashion, he used a low-tech printing method to multi-print low-cost, easily accessible and affordable art books for the general public.

The artist’s book ‘Snow Bleaching’ archives a particular area of my Washi paper research, which I felt represented the mutuality with and empathy for the landscape that the heritage paper production has. Traditionally, as part of the Washi paper production, the bark is stripped and separated, then laid out in the winter months across local snowy hillsides and in full sunshine. The reaction of the fibres to the snow below, the bright sunlight above and the naturally occurring ozone bleaches the inner bark. This is in stark contrast to wood-based pulp papers that use chemical bleaches to whiten the paper. Snow bleaching has been practiced historically for centuries in Japan, and is also used for bleaching traditional Washi textiles. Snow is significantly symbolic in Japan, representing purity and acknowledging its fragility and transience, a recurring theme that I will be developing in my work.

Printed on Washi paper, the artist book ‘Snow Bleaching’ is an iteration of the work carried out in my sketchbooks that led to the creation of the relief panel works of the same title. It offers an insight into the journey of developing the work from concept to visual outcome and is physically produced as a concertinaed laporella. I chose the laporella format as it unfolds to reveal itself as did the research, narratives and forms when I was exploring the subject area.

In homage to Edward Rusha, by offering the artist’s book on the website as a downloadable A3 document to self-print and assemble, the work becomes freely accessible to an international audience on a low-cost print-on-demand basis, or as a paper-free digital experience.

Your academic articles and collaborations span a range of disciplines, from cognitive neuroscience to cultural geography. How have these interdisciplinary experiences influenced your perspective as a sculptor, and do you see any intersections between your academic pursuits and your artistic practice?

I increasingly find that academic pursuit and artistic practice are intrinsically linked, with each responding and informing the other. As conceptual academic research into a subject matter gives rise to sculptural concepts, the practical results feed back into the research, producing a creative cycle in which theory and practice build upon one another. The devised nature of this style of practice means the outcomes are not pre-determined and have their own natural evolution.

Often, my analytical style of enquiry is driven by a need to fully understand the cultural and political context of a subject area. As a visual learner, mapping out histories and routes, be they literally represented or abstractly interpreted, helps me to comprehensively understand the cultural contexts and political landscapes of the narrative I’m concerned with. Creating a research landscape to seed ideas and grow the work from is intrinsic to my practice.

My sculptural work can cross a range of disciplines, and include collaborations with practitioners from other disciplines, resulting in sound and object installations and artists’ publications, but at its core is a curiosity and fascination with materials, fabrication, process and archive and, increasingly, environmental concerns.

In your opinion, what is the role of art in the contemporary atmosphere, and how do you see yourself as an artist within this role?

I see art as inseparable from politics and societal issues. I believe that, regardless of the creative lens employed, there is always some degree of ideological messaging, which offers fresh insights and provokes reflection and response. Art has always had the power to connect with communities and individuals, often transcending language, confirming to audiences or alerting them to the shared experiences of the human condition, and challenging pre-conceptions of what the lived experience could and should be.

I believe that being aware of the global impact of human activity on the climate and the planet’s eco-system will increasingly become the responsibility of the artist to engage with, whether it becomes a direct narrative in their work or not.

I see myself as an artist who can initiate debate around the impact of the Anthropocene, acknowledging the unprecedented impact humans are having on the earth’s environment by gently engaging and drawing audiences in with aesthetically pleasing and poetically gentle artworks, and then, once engaged, taking the opportunity to raise some of the challenging questions regarding the environment that need to be addressed.

Looking ahead, what are some future directions or projects you're excited to explore in your sculptural practice?

I will be exploring the possibilities of sustainable artistic expression using Washi paper further and exploring other organically produced and natural materials. I will be making some sculptural work on much a larger scale, and developing cross-disciplinary installation work, possibly drawing on the archive created in Japan. I am interested in exploring the fibre’s cellular structure to see if there are any commonalities between material and the landscape that come to light and which could lead to further material-focussed projects.

I hope to collaborate with similarly minded eco-artists and environmental scientists to develop a variety of new ways of communicating shared environmental themes. I'm also considering looking into ways of creating time-based artworks that visually convey the vulnerability of our eco-system through the ephemerality and fragility of the paper.

I aim to create art that is aesthetically beautiful, reflective and engaging, and that exists in harmony with nature.

What message or call to action would you like to leave our readers with?

As artists, I believe it is crucial to endeavour to reduce the negative effects we have on the environment, through the decisions we make in our practice, asking questions about the materials and processes we use and how they are sourced, and reflecting on whether or not we are adding to the negative impacts humanity has on our planet and acknowledging the impact of globalisation on communities.

Our art has the potential to open up discourses across many platforms and to be a voice for positive and progressive environmental change.

Go have a look at the artist website here and Instagram here

Cover image:

Heritage washi paper vessels by Dot Young. Image courtesy of Dot Young.

_Lauren%20Saunders.jpg)